While Uganda’s central region enjoys consistent rains in March, the dry season is upon Teso sub-region in eastern Uganda. Many rural communities have endured the worst of a hot, dry spell. The soils have been baked dry, the grass in most grazing fields has wilted, and most water sources – including wells, bore holes and valley dams – are drying up.

In the relentlessly searing heat, herds of cattle can be seen cooling themselves under thorny shrubs rather than grazing, while women rolling bicycles in hunt for water from the few surviving water points are common sights in most areas of Katakwi district.

Currently, out of the 28 boreholes in the sub county of Ongongoja, Katakwi district, only 11 have withstood the drought and remain operational. The other 17 are out of use after running dry as result of excess heat

of the last 6 month, locals here attest.

Images of parched valley dams seemingly sum up the water crisis faced by locals of Ongongoja Sub County, a shortage which has not only affected their lifestyle but has also compromised on their sanitation.

Ongongoja Sub County is a flat terrain, with a hard rock underground. It’s

also home to more than 18,000 inhabitants who are solely dependent on rain-fed water for both domestic use and agriculture. Consequently, the erratic rainfall patterns have brought added uncertainty for families and farmers, with the increasing population pressure on scarce resources such as food and water making the situation ever grimmer.

According to Susan Apule, a resident of Angolekit parish, Ongongoja Sub

County, the hustle for water hustle in this otherwise laid-back village often worsens whenever the dry spell set in early.

“The current dry spell we are experiencing has brought with it

untold suffering,” she said. “We have to brave hot days to draw water from the only one surviving borehole in this parish.”

The mother of eight says that due to the dry spell, she has had to scale back on using the little water available for household activities such as regularly bathing, and washing clothes or utensils.

“The little water we come a cross has much important roles to play than wash bed sheets. The key things we have to take care of now are water for cooking, for drinking, and animals. Bathing is now luxury to some of us,” she explained stoically.

To Apule, anyone who wants to avoid the long queues at the borehole during

the day has to spend nights at the water source. Since collection of water is normally a role assigned to women, it means that they are not only overworked (since they have to cook and do other household chores during the day), but they also miss bonding moments with their husbands, children or other family members.

“Like many other women faced with this plight, I am praying for the return of rains. We have had the worst of the dry spell, since November 2018. The water crisis continues to worsen,” she lamented.

The water crisis has not affected human being alone, says Francis Ipangit, a herder in Obwobwo, who says virtually all the valley dams built for watering animals are out of water. The only ones that continue to operate are those that were recently built by government in Aumoi.

“We struggle to water our herds at the same boreholes where we draw water for our domestic use,” he reveals.

Mr Ipangit says his worry is that even the Aumoi dam that is yet to be handed over to the community, has seen its waters also drop down.

“With this sharp drop in the volume of water, with no clear return of rains, we have to brace for harder times ahead,” he said.

The area LC3 Chairman, William Omeke, confirms that six key valley dams have dried up due to the long dry spell, which started in November of 2018. According to Mr Omeke, this means the pressure exerted on 11 surviving boreholes has doubled since they are now serving both human beings and their animals.

“What we ask of government is to have the valley dams de-silted,” he said. “The situation here is not good. Pupils at Ongongoja primary school have no

water source for both sanitary purposes and drinking, so attendance keeps dropping, especially for the girl children.”

The district water officer, Ms Lydia Eseza Apio, says the water crisis in Ongongoja is not out of neglect for the area. She said while the government has constructed boreholes for the sub county, the hard rock underneath its surface limits the sinking of boreholes.

“Last year alone, the government earmarked the sinking of four boreholes, but when the works got underway, the sites selected were not successful. No water sprouted from any of the sites,” she added.

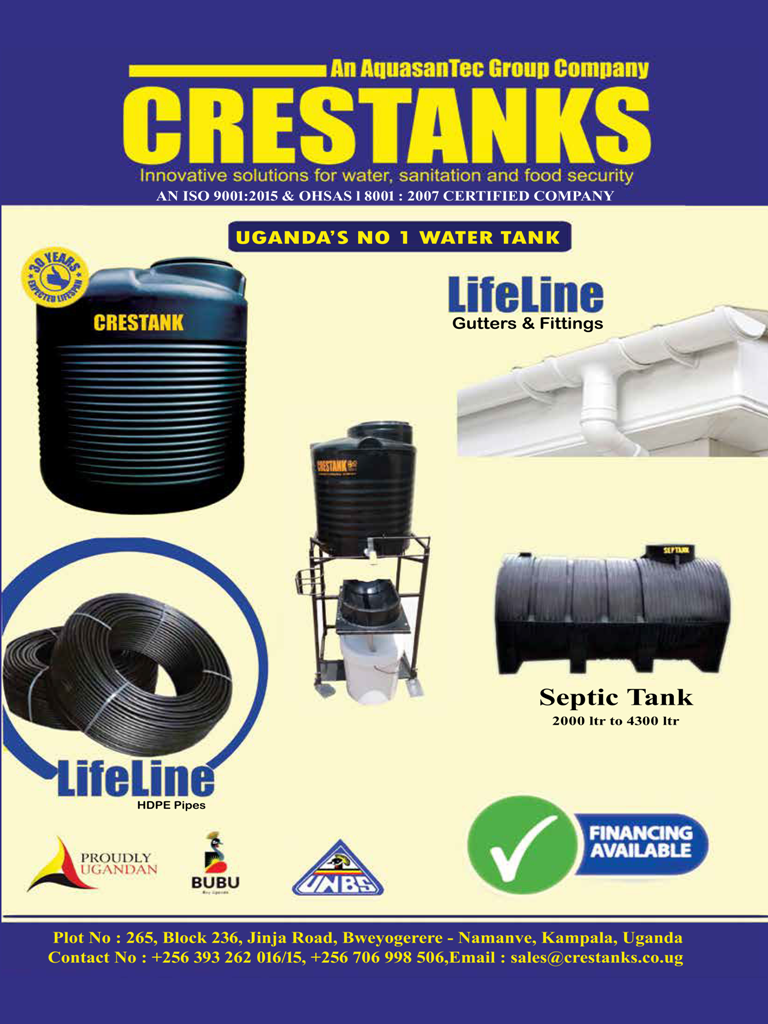

Apio says that 250 water tanks were budgeted for, but being a dry spell when there are no rains, the tanks are currently redundant.

However, this water crisis is not limited to only Ongongoja. Katakwi town

council is equally hard-hit as the water supply system has failed to match the sharp rise in the number of urban dwellers.

At Katakwi primary school, Mr Charles Ocailap, the head teacher, says the water crisis has affected service provision both at the school kitchen and sanitation among the girls who undergo menstruation.

“The water in our school taps only lasts for 45 minutes in the early morning hours until the next day. We have no borehole, we have to escort the pupils at 5pm to the nearest water source where we spend over six hours

struggling to draw water,” he narrates.

Ms Jennifer Ikaat, the senior woman teacher at St. Precissila Secondary School in Katakwi town, says the absence of a reliable water supply system impedes how they conduct their lessons.

“Our children and teachers brave thirst for hours. It is worse for the girl child undergoing her periods,” she says.

The manager Katakwi water supply system, Yusuf Waiswa, says the reservoir supplying water to the town dwellers is a 10,000-litre facility which can’t meet the bigger demand of the locals and surrounding institutions. “We need a reservoir with a capacity of about one million litres to meet the demand of this growing town,” he concludes.